Public Displays of Affection

In this unit, we deal first (Comprehension 1) with a topic that is immediately obvious to students: public displays of affection (PDA). On page 47, an Italian, an American and a French respondent each share experiences. Italian Nadia talks about holding hands and kissing on the street. American Trevor states that for him, PDAs are OK anywhere, anytime: he is happy to “allow people to see that I love her very much.” But not all cultures are so open about affection. French Jacques explains that when he was living in the US he was actually shocked at the way young American couples display intimacy through “holding each other, kissing, and calling each other cute names”. He felt they were “all over each other”.

“Get a room!”

Indeed, as Raymonde Carroll explains in the chapter on Couples in her excellent book Cultural misunderstandings : the French-American experience, French people distinguish strongly between two situations. One is when you are with your partner in public, surrounded by strangers, and the other is when you are out with friends. While people in French culture generally have no qualms about kissing in public, they frown upon obvious expressions of intimacy when couples are with their friends, family or other people they are close to. Says Jacques: “In France, that behavior is considered quite rude by people you are with (your friends or your family), as if you are excluding them or ignoring them. So, French people can be extremely individualistic when surrounded by strangers (“We are what we are, so what?”) but rather collectivist when they socialize. Overly affectionate people will be told to “get a room”. So, couples express their intimacy in more indirect ways, like allowing oneself to intervene into their partner’s behavior (“I think you drank enough for tonight, darling”) or contradicting each other in debate or even while discussing more practical matters. This kind of doesn’t fail to shock American couples, who would feel uncomfortable to be around such scenes, because for them contradiction in public is tantamount to a conflict.

The triangle model of cultural comparison

This is another interesting discovery that Japanese students can make, going further against the misguided notion that all Western cultures are alike. A triangular model replaces the usual us/them dichotomy :

- Americans and French people both behave in quite individualistic ways when they are surrounded by strangers in a public space, yet

- French and Japanese people control their “PDA behavior” to a large extent when they are in the presence of friends and family (even if there are considerable differences in the way people from these two cultures do this.)

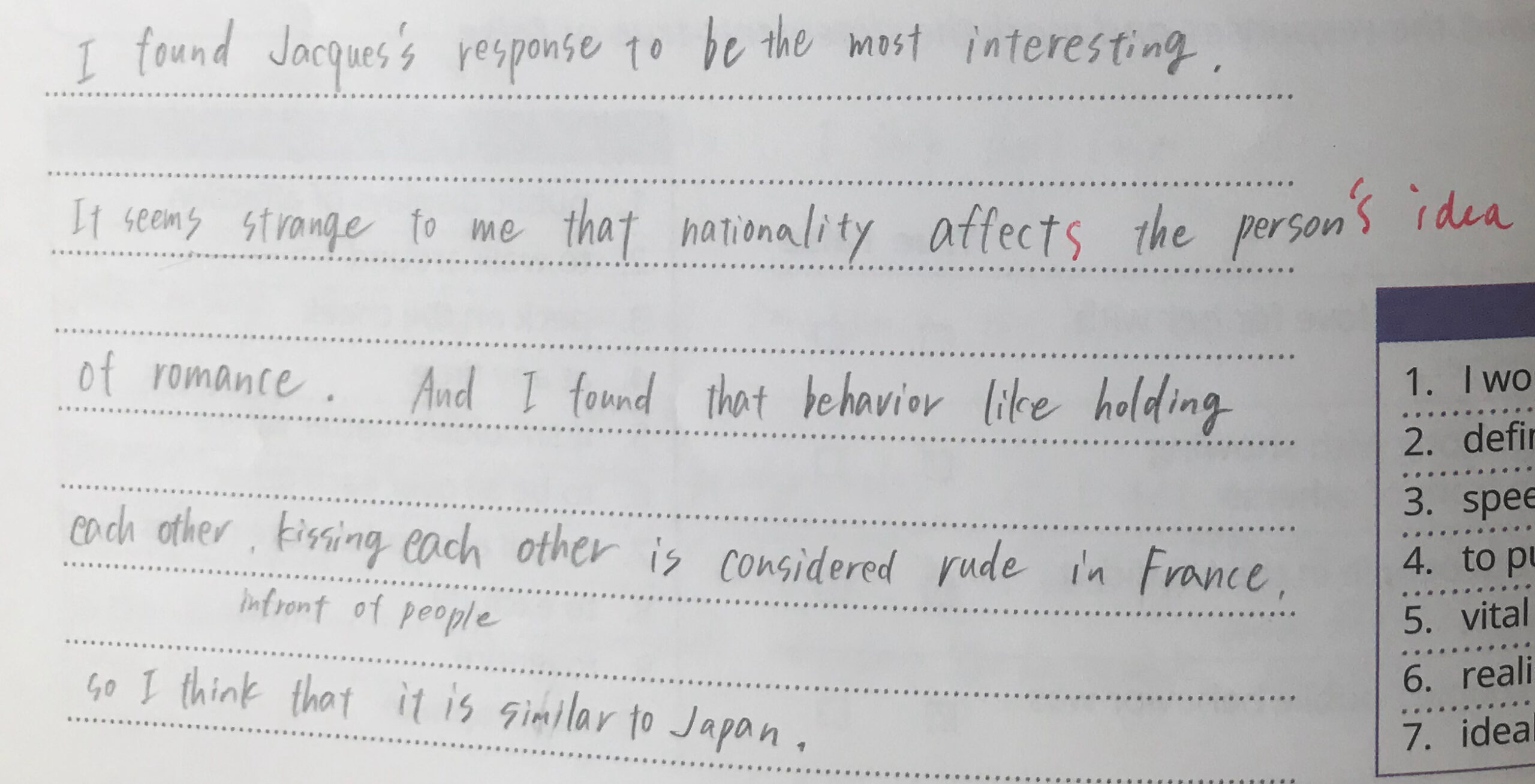

| In the Discussion activity, this student chose French respondent’s Jacques as the one that was most interesting to her. She noticed that some aspects of French culture are similar to Japanese culture. But it’s not clear whether she caught the fact that PDAs are accepted in France in the presence of strangers: “in front of people,” is not very clear. If she had written “in front of friends, or in front of people they know”, it would have been clearer. |  |

Reading each other’s minds

The unit then moves on to a deeper topic- how do couples expect to manage the everyday details of their relationship? Do they express their needs clearly and directly, or do they prefer to rely on more tacit understanding?

Hungarian Hanna and Swiss Mila express a view of communication between partners which seems to be common in many Western cultures: “I think that being able to listen to each other’s opinions and requests is one of the most vital things in a relationship”, “For me, it’s only after having a good discussion that you can really empathize with someone. If you just try to guess their feelings, the chances are high that you’ll be mistaken a lot of the time.”

On the other hand, Japanese respondents Maho and Takeru express a different preference: “I feel that if he truly loves me, he should take the time to notice my needs”, “I wish he could “read the air” a little better”, and “I feel that I shouldn’t have to explain everything to her.” For them, words shouldn’t be so necessary in an intimate relationship. Spelling everything out in detail feels rather cold to them, almost as if their partner wasn’t interested in trying to understand them intuitively. Another Japanese respondent in the OSF section (No. 5) backs this up when she says that for her, “being too analytical takes some of the romance out of a relationship.”

In this section, that encompasses Comprehension 2 and Culture Shock, Japanese culture is contrasted with the West as a whole. There actually are deep cultural variations between Western countries, for example between the American and European styles of communication between partners: the degree to which disagreement is accepted, the directeness or indirectness of expressing requests (see Unit 10: Asking a Favor), how directly you express feelings, and the acceptance of sarcasm, humor and irony, amongst others.

In the One Step Further section, a Chinese respondent echoes the Japanese predominant cultural pattern: “When I think about it, maybe in reality what I really want is for my husband to guess my needs”.

Having friends in common

The One Step Further section for this unit covers two topics. The first is about communication styles: “Understanding through discussion” versus “Understanding without words.” The second is more about social or lifestyle preferences: “Having friends in common” versus. “Having separate friends is more comfortable”.

- A Japanese respondent states that for her, “We don’t have any friends in common because we went to different universities and work at different companies. It doesn’t matter if we share friends or not”.

- A Croatian respondent shares that she finds it “surprisingly difficult to get (her Japanese partner’s) to meet (her) friends.”

- An American informant reports that he doesn’t have any friends in common with his Japanese wife, in the meaning of having not only a common bond, but also diadic bonds between him and each of them (which seems to be his meaning for “the traditional sense” of the meaning of “friends”). But it’s worth noting that he seems to indicate meeting his friends in the presence of his wife, and that the reverse is also true. Many other responses we got in the Ibunka Survey were by Westerners complaining that they missed not having friends in common with their Japanese spouse. In Japan, a common reaction seems to be “Why don’t you go out with your friends? They’re yours, and not mine.” It seems that the boundaries of groups (spouse, family, friends, co-workers, etc) are quite differently drawn according to culture.

This issue is also connected to the topic of the house (Unit 4, Having Guests in your Home). It seems that when socializing is done in places outside of the home, the idea of partners having their own unconnected social groups is more natural.

| Symmetrical and complementary relationships This points to another cultural dimension of couple relationships which could be described as the level of symmetry or complementarity which is viewed as desirable. Gregory Bateson introduced this continuum in his book Steps to an Ecology of Mind. He suggests that symmetric relationships, in which partners adopt the same type of behavior, can become explosive as symmetry implies competition. On the other hand, complementary relationships, in which partners adopt separate but complementary roles (“You take care of this, and I take care of that”, “You go there and I’ll stay here”, or “I’ll guess your needs and you guess mine”), naturally generates difference. Bateson notes that sometimes even a touch of symmetry brings balance to otherwise heavily complementary relationships. He gives the example from Medieval England, with its extremely top-down societal hierarchy, in which lords dominated the masses, who had very few rights and many burdens. In some areas, lords and commoners would meet for an annual soccer game, in which all of them would play in the mud, following the same rules and doing their best to win. He hypothesizes that those rare events had a strong effect in keeping the system stable, by introducing a touch of symmetry, therefore making the prevailing complementarity more bearable. In the same vein, when couples invite friends to their home they naturally find themselves in the same place, meeting the same people and having a common experience. This experience is one of the forces that molds relationships because they bring the partners into a symmetric interaction, even if their lives are by and large in a complementary dynamic. In the Ibunka Survey, a number of foreigners married to Japanese people have admitted their frustration with not being able to invite friends to their homes and thereby socialize “naturally” together with their spouse. |

References and further reading

- Carroll, R. (1988), Cultural Misunderstandings : the French-American experience, Chicago : University of Chicago Press

- Bateson, G. (1972), Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology. University of Chicago Press

- Vannieu, B. Furansujin kara mita nihon no danjō kankei, in Fujita, T and Doi, I (eds.)(2000) Onna to Otoko no Shadō Wāku, Nakanishiya Shuppan. (in Japanese)