This unit is dedicated to the cultural act of conversation, and the ways in which we go about talking with others. What seems “natural” to us about what, when, and how much to say is actually deeply ingrained in our culture. We have all unconsciously learnt and internalized the rules of our native languages and home societies. Living abroad, we come to terms with communicating according to the rules of the culture around us. We learn to conduct conversation and discussion in different ways.

Many questions and answers, or longer, more spontaneous talk?

In Japan, it is common for conversation partners, especially people who don’t know each other well, to take turns asking each other many questions. Brief answers are an invitation to ask the next question. As people are carefully looking for common ground, this is seen as the safest, most respectful way to conduct yourself. However, in many Western cultures, it is largely true that a minimal answer like “No” to a closed question such as “Do you have a part-time job?” implies that the responder is not interested in conversing.

In our oral communication textbook Conversations in Class, we explain to students that giving longer answers when speaking in English is a way of showing interest in conversation. It is considered cooperative and polite to volunteer extra pieces of information for the listener, giving them little “hooks” to latch onto by asking follow-up questions.

The Polish respondent on page 88 (OSF No. 2) says “When I am with my friends, I speak about myself without being asked questions, and also expect them to do the same even without asking.” Her testimonial hints at the cultural habit, common in the Western world, to speak from oneself, about oneself, as a way to volunteer information and to invite your conversation partner to speak. This is a very powerful, but somehow hidden, aspect of communication which deeply influences the way we interact with others.

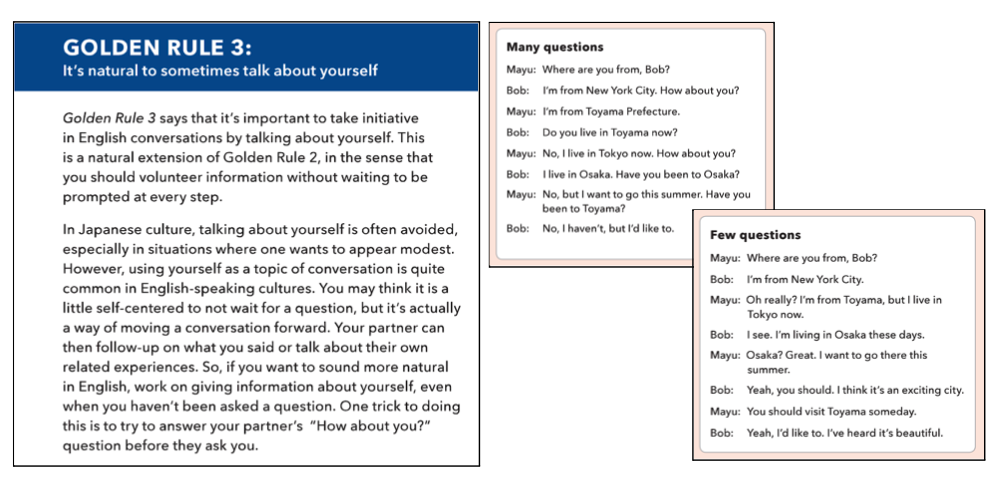

| Integrating the “Western cultural codes of conversation” into Japanese oral communication classes In our oral communication textbook Conversations in Class, our goal is to (1) unblock uncommunicative students who have never had an actual two-way conversation, (2) have them practice basic conversation patterns that are suited to basic, everyday conversations in English. We give them three cultural “Golden Rules” and encourage them to incorporate them into repeated practice. This must be repeated because taking on such habits requires time, as our habits or “scripts” for conversation are cultural and therefore deeply ingrained. The three Golden Rules that we encourage students to follow are: GR1: Don’t remain silent more than a few seconds → How? By making “thinking sounds”, repeating the question, asking to clarify the question, asking for help in formulating an answer, saying you don’t know, etc. GR2: Give long answers → How? By replying to at least one implicit question contained in the explicit question. GR3: Speak from yourself → How? By answering your partner’s “How about you?” question before they ask you, or by rebounding on what someone said by speaking about oneself on the same topic.  |

How cool are you with disagreement?

The Comprehension 2 and Culture Shock sections look at the topic of disagreement or contradiction within discussions.

- Japanese respondent Juri talks on page 54 about her experience with French people having a rather animated discussion. She was shocked when she thought her French boyfriend and his friend were having a fight. Their tone was probably elevated, their debating rapiers unsheathed, and their gaze intense, they interrupted each other constantly. But it turned out that they were just having fun contradicting each other, and they were surprised at her emotional reaction.

- On page 55, Italian Vincenzo shares his experience of living in the US. Like Juri’s French boyfriend, and members of other Latin cultures, he views interrupting as an expression of interest in what the discussion partner is saying. As he admits, “I can’t help but jump in.”

- Japanese respondent Juri talks on page 54 about her experience with French people having a rather animated discussion. She was shocked when she thought her French boyfriend and his friend were having a fight. Their tone was probably elevated, their debating rapiers unsheathed, and their gaze intense, they interrupted each other constantly. But it turned out that they were just having fun contradicting each other, and they were surprised at her emotional reaction.

- On page 55, Italian Vincenzo shares his experience of living in the US. Like Juri’s French boyfriend, and members of other Latin cultures, he views interrupting as an expression of interest in what the discussion partner is saying. As he admits, “I can’t help but jump in.”

| Raymonde Carroll gives a great description of the processes involved during a discussion by French people (and by extension people from Latin cultures): discussion partners keep steady eye contact with the persons they are talking with, to gauge their interest and be aware of their desire to speakWhen someone wants to speak, intervene, they first start with non-verbal clues (like leaning forward, opening their mouth as though they are going to speak) and verbal clues (starting a sentence but not finishing it: “Yes, but…”).Participants’ tone is getting more and more animated; there is a real group warming up and people get “agitated” (when seen from an American point of view); the speed is increasing.Contradiction is not avoided, and even welcomed as it makes for more interesting dialectics. But nobody takes it personally: one’s position on a topic and one’s affection or respect for the conversation partners are obviously two different things. One doesn’t automatically want to side with one’s friends or romantic partner during a discussion just because of personal or social ties. Vincenzo finds the American style of discussion boring:Americans dislike being interrupted, which lack of respect (“Let me finish!”)They therefore have longer turns of speech.Their voice tone is calmer, lest they wouldn’t mind signaling tension or anger.They don’t need to maintain constant eye contact, not expecting to have to gauge whether they can go on or if they should speed up / change the direction of what they are saying / let someone else intervene. |

- Andrew (page 54) is Australian, but his communication style seems to be in line with those of the American respondents to our survey. In his culture, as he has experienced it, open disagreement is not taken very well. It can be equated with conflict, and is synonymous with pressure. He says: “In Australia, disagreement can often be seen as disrespectful and quite arrogant, I think.”

- The Spanish respondent (OSF no.6 on page 89) adds that in her experience Japanese people “clam up” when she talks about abstract subjects: “They quickly clam up so as to say nothing that could go against my ideas.” It makes her feel “uncomfortable” because “This makes me feel like I’m forcing them to accept my point of view.” The same Spanish respondent suggests that having open discussions with people is a necessary part of friendship. “For me to become friends with someone, conversation and discussion are important. I need to feel there is mutual trust between us, and that entails being able to broach almost any topic.” The French respondent (OSF no.7) explains: “I like to discover different points of view on a subject or a situation, even if I don’t completely agree. It gives me a fresh perspective on the subjects in question.”

- One Chinese respondent (OSF no.9) suggests that, in her experience of her home culture, people would tend to be closer to Japanese culture, as far as the expression of disagreement is concerned.

Not all Westerners have the same discussion style

Americans and French people (or other people raised in Latin cultures) therefore have a lot of potential for culture shock when interacting with each other (they comment that their conversion partner was “rude”, “boring”, “didn’t show any interest in what I was saying”, “didn’t open the discussion and try to include me”, etc.)

This is potentially another interesting discovery for Japanese students, who can relate to either one or the other cultural styles of discussion. By and large, they are not accustomed to the act of discussing and debating abstract ideas. But it is good for them to realize that there are very distinct styles among Western cultures, and that even if general tendencies are shared (that it’s OK to talk about ideas and to accept some contradictions), there are subtle cultural rules that one needs to follow in order to communicate effectively in the culture in question. French people are careful of their discussion partners’ feelings, they respect certain ways of formulating their ideas (contradicting someone’s idea on an abstract topic is not a personal attack ) and certain ways to influence the speaking turns of all people present.

References and further reading

- The Communicative Advantages of Interrupting (Psychology Today article)

- Talandis, J., Vannieu, B., Richmond, S. (2015), Conversations in Class, Third Edition. Kyoto: Alma Publishing (Golden Rules)